|

|

|

Conservation of Archeology sites in Urban Areas

Preservation of Antiquity Sites in an Urban Context – Karmiel as a Test Case

Zvi Gal

Introduction

Most of the antiquity sites that have been properly protected in Israel are currently located in national parks, and only a few are in other types of facilities. Their preservation was made possible thanks to their legally having been declared a national park (the Law of the Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority) or their having being designated archaeological parks in the town building plan. There are no more than seventy such sites and their preservation was facilitated by their being located outside urban settlements.

The dramatic growth of Israel’s population since the beginning of the 1990’s has resulted in a substantial increase in the rate of development and expansion into areas with rural, semi-urban and urban settlements. At the same time, society's values and government goals also changed, culminating in privatization measures and sanctification of real estate interests that were applied to cultural assets as well. This new reality poses a challenge to the preservation of cultural heritage in general and antiquity sites located within the domain of urban settlements in particular.

Cultural heritage/site management is a world wide issue, and those who deal with it, both on the theoretical and the practical level, are convinced that public and local government involvement in this activity is of utmost importance. In Israel, the establishment that can most influence the procedures for preserving antiquity sites is the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Sites of major importance or those located in open spaces are easier for the Antiquities Authority to deal with; when they are minor and local or located within the domain of urban settlements they pose greater difficulty. Unfortunately, most of the endangered sites in urban settlements are, [1] in fact, minor and local, and therefore their preservation constitutes a greater challenge.

The town of Karmiel, where there is an especially large concentration of antiquity sites, is a test case for a landscape unit in the midst of enormous development. It is rapidly changing from an open area to a dense urban fabric whose development (to which there are many partners, all with different agendas) jeopardizes the antiquity sites located within its bounds.

|

|

|

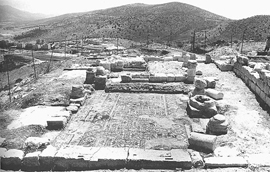

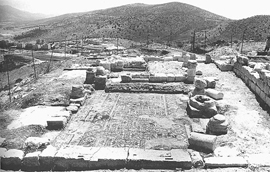

Figure 2

|

Karmiel as a Test Case

The natural landscape of Karmiel and its historic sites is characterized by rocky limestone and dolomite hills separated by tiny valleys. Guérin (1985:303-307) describes the region as covered with ancient olive trees and shrubbery consisting of mastic trees, Palestine pistachios and calliprinos oaks. Until the founding of Karmiel in the beginning of the 1960’s, eight sites were located within what would eventually be the municipal limits of the town. Noteworthy among them are: Horbat Bata, Horbat Qav, Horbat Zaggag and Horbat Kenes, as well as Khirbet Madrasa and Khirbet el-Qabra ( Fig. 1).

In addition to these, there were a number of smaller sites and burial caves that were situated mainly in the Sagi neighborhood. Additionally, in the Ramat Rabin quarter in the south of the town is a tiny, extraordinary site that dates to the Iron Age 1. Guérin visited only some of these sites in 1860 - there were so many of them that he was probably unable to stop at each one during a single day of surveying (Guérin 1983:303-307). A similar number of sites is designated on Sheets III-VI of the Survey of Western Palestine and it seems that the survey team visited the principal ones among them. It should be pointed out that these are all Christian Byzantine sites, constituting one of the densest concentrations of Christian sites in a given area. This is almost unparalleled in the western Galilee, even though most of it was inhabited by Christians during this period (Aviam 2004).

In the 1930’s and 1940’s, many years prior to the founding of Karmiel, some of the hills on which the town was subsequently established, were used as stone quarries that left the landscape damaged and scarred. This matter is of considerable importance in light of the use that was made of this quarry landscape in developing the Galilee Park in the town (see below).

A perusal of various documents in the archives of the Antiquities Authority shows that on the eve of the town’s founding in 1964, meetings were held between representatives of the Department of Antiquities and the Ministry of Construction and Housing in order to coordinate development plans. However, construction in the field outpaced the understandings that had been reached, resulting in damage to some sites and the complete destruction of two of them (Khirbet et-Thahar and Horbat Rahaz). [2]

At the same time there was an understanding in principal between the Department of Antiquities and the Ministry of Construction and Housing that archaeological excavations would be carried out over the course of two to three years. Even though this arrangement was not fully implemented, an archaeological excavation, in which local school children participated, was begun at Horbat Bata and continued for several years.

The objective, as was the custom at that time, was to foster a connection between the youth and their surroundings through the experience of discovering the ancient remains and then integrating them into a municipal park. [3]

During the course of the excavation, a monastery, a church, mosaics and a large water cistern were discovered (Fig. 2; Yeivin 1991). Even though the remains that were uncovered were impressive and quite well preserved, neither their conservation nor the idea of integrating them into the plans for the surrounding development were pursued.

|

In 1984, twenty years after the founding of Karmiel, an archaeological survey was conducted within the slated municipal limits of the town.[4] As a result of the survey, Horbat Bata, Horbat Zaggag and Horbat Qav were incorporated in the town’s master plan as protected antiquity sites that should not be touched. Despite this, no plan was ever formulated as to what can and should be done with them. The other sites were not granted similar status and the formulation of policy concerning what can and cannot be done to them, including assessing their value, was not done until the early 1990’s, when the thrust of the construction began to encroach and because of the new powers invested in the Antiquities Authority.

As previously mentioned, the wave of development began in the town in the early 1990’s and has continued until the present day. Within this framework, the Ministry of Construction and Housing embarked upon extensive construction in the western and southern parts of the town, in an area where Horbat Zaggag, Horbat Qav, Horbat Kenes and the Iron Age site are located.

At this time, the Antiquities Authority was established and began operating. It quickly became clear that it was impossible to present any compelling reservations concerning the development plans because these had been approved many years earlier. Therefore the Antiquities Authority permitted the construction conditional to the carrying out of salvage excavations, knowing fully well that after their completion the building plans would be implemented. Nevertheless, several initiatives were undertaken that were intended to ensure the preservation of a number of small sites.

|

Sagi Neighborhood

In the Sagi neighborhood are remains of a small monastery whose foundations are visible on the surface. The site is included in one of the lots slated for construction. In view of the building’s fine state of preservation and the probability of there being mosaic floors within, the Ministry of Housing responded favorably to a request by the Antiquities Authority and modified the designation of the lot where the monastery is located, changing it to an open public area. This thoughtful act saved the monastery, yet no other development measures were taken there, despite a number of ideas that were submitted that do not involve an archaeological excavation.

|

Horbat Kenes

Megadim School was constructed on Horbat Kenes years ago.A recent planned enlargement threatened the antiquities located at the site. The salvage excavation that was conducted there exposed a large church which contained breathtakingly beautiful mosaics (Aviam and Avshalom-Gorni 1995; Fig. 3).

In light of these discoveries, the Antiquities Authority denied permission to demolish the building and suggested it be integrated into the school’s compound. Regrettably, despite the site’s fine state of preservation and the high quality of the mosaics in it, no funding has yet been allocated for the completion of the excavation and the conservation and development of the site, while the ancient building stands covered in the middle of the compound. Even though the site was not destroyed, the solution that was arrived at was, to say the least, extremely wanting.

The remains of the church and particularly its mosaics have not been treated properly and, as things stand, the antiquities constitute an obstacle inside the school compound which conversely threatens the totality of the antiquities site.

|

|

|

Figure 4 - Horbat Qav

|

Horbat Qav

Nasiei Israel Boulevard, one of the town’s main streets, was planned to extend across the outer precincts of Horbat Qav, and prior to its construction a salvage excavation was conducted along a small part of the site in 1990 (Gurin and Stern 1994). Sometime later, the Ministry of Construction and Housing requested permission to develop a large public park within the confines of the site that involved remodeling the landscape of the hill; however, they did not have a specific plan for the treatment of the antiquities that were there.

The Antiquities Authority stipulated its approval for the plan of the park conditional on carrying out an excavation at the site and integrating its remains in the park as a central component. The Ministry of Construction and Housing, realizing the value of the site, agreed to shoulder the responsibility for the planning and the financial burden. A fruitful dialogue occurred between the park’s planners and the Antiquities Authority which ultimately produced a plan that was satisfactory to all parties concerned. As a result, archaeological excavations were conducted, revealing the remains of a monastery in which there is a small church and a large wine press adjacent to it (Abu Uqsa and Stern 2001); these were properly preserved and basic conservation measures were also implemented in the Ottoman building that is also located at the site.

Today the park at Horbat Qav nicely incorporates the ancient remains with the modern development while safeguarding the characteristics of the original landscape (Fig. 4).

|

|

|

Figure 5,6

|

The Iron Age 1 Site

The manner in which the Iron Age site located south of the town was treated raises serious questions regarding the ranking of sites.

The site was not identified as worthy of preservation in the town’s master plan, even though it is particularly important since it is one of the few Iron 1 sites located in this part of the Lower Galilee. The building plans that were presented to the Antiquities Authority were actually already completed and were based on permits issued years earlier. In view of this, it was agreed by the Antiquities Authority and the Ministry of Construction and Housing that destruction of the site should be prevented by covering it with soil, but this would be done only after a partial salvage excavation was conducted in order to document some of the remains (Gal and Shalem 1999; Gal, Hartal and Shalem forthcoming).

Already after the first season of excavations it became clear that not only was the site better preserved than expected, but that its connection to its immediate surroundings is part of its history. It is located at the foot of a rocky outcrop. To its east extends a small valley in which are small tracts that were cultivated until recently, just as they were in the past, by the Bedouin. Each winter, the run-off water accumulates in a pond in the middle of the valley that was used in antiquity, as it is today, by both man and animals (Figs. 5,6).

Actually, the site and its surroundings, until modern development, were undoubtedly a credible reflection of how the region’s landscape appeared in antiquity; this further increased its value and importance.[5]

|

|

|

Figure 7

|

In retrospect, it turns out that, in view of the archaeological importance of the site, its relative rarity and its fine state of preservation, it would have been more appropriate to insist that it be preserved rather than covered over. However, the preservation of the site would have been of practical value only against the backdrop of its original surrounding landscape – the rocky peak to its west and the small valley to its east. It is possible that, had the sites been ranked while they were still in the beginning stages of the town planning, it would have been possible to ensure the preservation of the site (or at least part of it). Unfortunately, the development work included drastic changes to the surrounding landscape during which the hill was removed and a school was built in its place; the site was covered with fill to a height of 8 m (Fig. 7) on which parking lots were paved, and in the small valley a new neighborhood is slated for construction. Therefore, even had it been possible to save the site from the bulldozer’s blade, it would have remained trapped inside a small island within a parking lot. Therefore, in the absence of any possibility of preserving the site within a substantial part of its surrounding landscape, our being satisfied with covering it and preventing its destruction seems the lesser of two evils.

|

|

|

Figure 8

|

Conclusions

Karmiel’s master plan was first drafted many years ago, when consciousness regarding the preservation of cultural heritage was only slight, and intervention by the Antiquities Department was also limited.

Nevertheless, we must evaluate the chain of events, the role of the various institutions whether in deed or through oversight, consider the consequences of the accelerated and intensive development on a large concentration of archaeological sites located within the town limits, and draw conclusions regarding the future.

Even though during the chain of events no evaluation was made of the different sites and their relative importance, the results seems to have been reasonable. Horbat Bata – the large and principal site – was not destroyed, although nothing was done to preserve the antiquities that were exposed there in the 1970’s. [6]

This central site has been severed from the surrounding regional landscape, the different neighborhoods are practically encroaching upon it, and to the southwest it is blocked by public buildings and a grove of trees (Fig. 8). Preventing the destruction of the small monastery in the Sagi neighborhood is also an example of minimal specific treatment, and today the lot where the monastery is located is a public park with no way of knowing what is concealed beneath its surface. On the other hand, it is obvious that the church at Horbat Kenes, which is located in the Megidim School compound, is neglected.

There is no doubt that, although ostensibly protected by a covering of earth, this in neither the desirable nor the proper solution. If the planning of the school had been done with an awareness of protecting the heritage and had the professional authorities been consulted about this matter, a better solution for the ancient structure would have been reached that would have integrated it properly in the compound. As mentioned above, Horbat Zagag was not destroyed.

Despite the fact that the area containing the antiquities is quite limited, the hill has not been touched and remains as it did in antiquity (Fig. 9); only a small look-out was erected on its peak. [7] Even though the site was protected, an early ranking and assessment of the sites would probably have assessed the relatively low value of the ruin. It then would have been possible to plan the area where it is located in a different manner and even permit some construction there. It probably also would have been possible to protect part of the Iron Age site and its immediate surroundings.

|

|

|

Figure 9 - Horbat Zagag

|

Of all these sites the treatment of Horbat Qav was indeed outstanding. As previously mentioned, the site was excavated but underwent conservation.

It was developed and today it stands in the center of an impressive municipal archaeological park. There is no doubt that in this instance, the cooperation between the Antiquities Authority, the Ministry of Housing and the Karmiel municipality provided a proper example whereby the need for development was balanced by the need to preserve the cultural heritage.

In conclusion, it seems that if the planning process had integrated considerations of heritage site administration rather than responding only to development plans, probably different and more correct conservation decisions would have been reached.

An examination of how the institutions operating in the area responded shows that the conservation of the antiquities at Karmiel began as a chain of responses by the Antiquities Authority to the development plans of the Ministry of Construction and Housing.

Only time and several mishaps along the way did the issue become a topic for dialogue between these two authorities. Despite the fact that the accepted models for preserving cultural heritage call for the participation by the local residents in the administration of the heritage asset and its conservation, this did not actually occur in this case. Even though the Karmiel municipality participated actively in the discussions, it did not fulfill a significant role and its attitude to the entire issue was rather passive. The impression was sometimes felt that it considered heritage preservation an obstacle that delays development – a surprising attitude today. [8] This is all the more unusual considering the fact that Karmiel is an amazingly well administered town which places tremendous emphasis on the design of its streets, parks and town squares.

|

|

|

Figure 10

|

The historic landscape on which Karmiel was founded was an integral part of the sites that were located in this area. However, the intensity of the regional development was and is occurring with such unprecedented drive – rocky hills were leveled and valleys were filled in with earth -- that practically none of the ancient landscape remains (or will remain).

For example, even though Horbat Bata and Horbat Zagag were not physically destroyed, they lost their singularity in the landscape and are lost inside the urban area. This situation is conspicuous when contrasted with Horbat Madrasa and Khirbet al-Kabra located at the western outskirts of the town. For various reasons the newly built-up areas of the nearby Giv’at Ram neighborhood have yet to reach them and their Galilee landscape still safeguards their features (Fig. 10).

Paradoxically it is interesting that the town planners preserved the area of the old quarries from the 1930’s (see above) for “Galilee Park”, a large public park in the town (Fig. 11). This approach created an absurdity where it was preferred to preserve the destruction that the modern quarries caused to the regional landscape rather than invest in preserving the cultural heritage. It is possible that this stemmed directly or indirectly from the desire to circumvent the need to cope with preserving the antiquity sites and avoid the financial investment which that entails.

That notwithstanding, if other antiquities were discovered among Karmiel’s sites (synagogues, for example) it is likely their treatment would have been different, the required budgets for their preservation would have been found much more easily and the flexibility in the planning would have been a lot greater. [9] This is not said merely for the sake of being critical but rather to stress that preserving our past heritage is a value in and of itself and remains that are not of a Jewish/nationalistic nature are, from a standpoint off cultural heritage, also worthy of preservation. Furthermore, the dense concentration of churches and monasteries in Karmiel is quite unparalleled, giving these antiquities tourism potential, one of the modern parameters for the proper administration of cultural heritage.

The experience at Karmiel demonstrates that the entities entrusted with the government’s planning policy and its methods of implementation have still not completely assimilated the necessity of integrating the management of the cultural heritage as an essential part of that policy. It also seems that the urban planners, working at the request of government ministries and according to their guidelines, have not internalized the need for preserving antiquities sites and incorporating them in the fabric of the modern development. The data are certainly available to them, but we rarely hear them calling for the preservation of cultural heritage, and the attitude that sometimes seems to prevail is one of searching for easy solutions under the heading of “nuisance elimination”. It is certainly true that preserving cultural heritage sites requires a budget, but experience has usually shown that when there is awareness the budget can also be found. The difficulty in that case is in the doubt that the subject of preservation will gain awareness during the era of the “new economy”, when the value of a tract of land is measured in dunams, dollars and time.

From this standpoint the results in Karmiel are unsatisfactory, even though they could have been much worse. And although the chain of events was seemingly reasonable, it does not lead to the conclusion that the steps that were taken there were the best and are likely to succeed elsewhere. On the contrary! We should not have to depend on the possibility that a representative of the government ministry operating in the field will see the broad picture. Rather, we have to ensure there is a built-in response, or at least some guideline, for managing cultural heritage and preserving the hundreds of antiquity sites scattered about the country. Such a measure needs to focus precisely on those secondary sites whose significance and importance are their diversity. For this reason, their preservation is essential, even though they will obviously never become national parks.

|

|

|

Figure 11

|

References

Abu-Uqsa H. and Stern E. 2001.

Horbat Qav. Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 116:16-18. (Hebrew).

Aviam M. 2004.

Jews, Pagans and Christians in the Galilee (Land of Galilee 1). Rochester. Pp. 181-204.

Aviam M. and Avshalom D. 1995.

Horbat Kenes. Hadashot Arkheologiyot -- Excavations and Surveys in Israel 103:21-23. (Hebrew).

Gal Z. and Shalem D. 1999.

Karmiel. Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 109:12-13. (Hebrew).

Gal Z., Hartal M. and Shalem D. Forthcoming.

An Iron Age Site at Karmiel, Lower Galilee. Gittin Festschrift.

Guérin V. 1985.

Description of the Land of Israel, The Galilee. Volume 6. Translated by H. Ben-Amran. Jerusalem. (Hebrew).

Gurin Y and Stern E. 1994.

Horbat Qav. Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 100:15. (Hebrew).

Onn A., Wexler-Bdolah S., Rapiano Y and Kanias T. 2003.

Khirbet Umm al-Umdan. Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel 114:74-78. (Hebrew).

Yeivin Z. 1991.

Excavations at Carmiel (Khirbet Bata). ‘Atiqot 21:109-128.

|

[1] Ranking the sites according to their importance is an issue that cannot be separated from preservation. The criteria for ranking the sites are varied and are characterized by national, local, cultural, historic and other aspects. It is clear that it is easier to formulate policy for sites that are ranked important than for the less significant ones. However, most of the sites fall between the two ends of the spectrum; hence the great challenge confronting those doing the ranking.

[2] A letter dated 7.4.63 written by M. Prausnitz, the district archaeologist for the Western Galilee, states that work was begun in the field without having first been coordinated with the Antiquities Department. G. Foerster, the district archaeologist for the Galilee, in a letter dated 1.7.65, records that two sites were severely damaged.

[3] According to Z. Yeivin, then deputy director of the Antiquities Department who directed the excavation at Horbat Bata.

[4] Israel Antiquities Authority archives. The survey was conducted by R. Frankel.

[5] This site is an excellent example of a tiny ancient site that is well-preserved although the physical conservation is quite difficult. Despite this, it is extremely valuable in the context of its surroundings and its period.

[6] In 1994 the site was thoroughly cleaned at the initiative of M. Aviam, then the district archaeologist of the Western Galilee. These measures greatly contributed to the maintenance of the site but since then nothing has been done.

[7] The site was recently excavated by the Galilee Archaeological Institute, under the direction of M. Aviam.

[8] In this context we should mention the active role taken by A. Shamir, the administrator of the northern district of the Ministry of Housing, who succeeded in seeing the broader picture, instructed his planners to cooperate with the Antiquities Authority and allocated the necessary budget for the excavations at Horbat Qav and for the development of the archaeological park there.

[9] This situation can be compared with the discovery of the synagogue at Khirbet Umm al-Umdan in Modi’in, in an area that was slated for development; the nature of the finds that were discovered in the excavations resulted in a change in the planning and in the preservation of the site (see Onn, Wexler-Bdolah, Rapiano and Kanias 2003).

[1] Ranking the sites according to their importance is an issue that cannot be separated from preservation. The criteria for ranking the sites are varied and are characterized by national, local, cultural, historic and other aspects. It is clear that it is easier to formulate policy for sites that are ranked important than for the less significant ones. However, most of the sites fall between the two ends of the spectrum; hence the great challenge confronting those doing the ranking.

[2] A letter dated 7.4.63 written by M. Prausnitz, the district archaeologist for the Western Galilee, states that work was begun in the field without having first been coordinated with the Antiquities Department. G. Foerster, the district archaeologist for the Galilee, in a letter dated 1.7.65, records that two sites were severely damaged.

[3] According to Z. Yeivin, then deputy director of the Antiquities Department who directed the excavation at Horbat Bata.

[4] Israel Antiquities Authority archives. The survey was conducted by R. Frankel.

[5] This site is an excellent example of a tiny ancient site that is well-preserved although the physical conservation is quite difficult. Despite this, it is extremely valuable in the context of its surroundings and its period.

[6] In 1994 the site was thoroughly cleaned at the initiative of M. Aviam, then the district archaeologist of the Western Galilee. These measures greatly contributed to the maintenance of the site but since then nothing has been done.

[7] The site was recently excavated by the Galilee Archaeological Institute, under the direction of M. Aviam.

[8] In this context we should mention the active role taken by A. Shamir, the administrator of the northern district of the Ministry of Housing, who succeeded in seeing the broader picture, instructed his planners to cooperate with the Antiquities Authority and allocated the necessary budget for the excavations at Horbat Qav and for the development of the archaeological park there.

[9] This situation can be compared with the discovery of the synagogue at Khirbet Umm al-Umdan in Modi’in, in an area that was slated for development; the nature of the finds that were discovered in the excavations resulted in a change in the planning and in the preservation of the site (see Onn, Wexler-Bdolah, Rapiano and Kanias 2003).

|

|

|

|

|